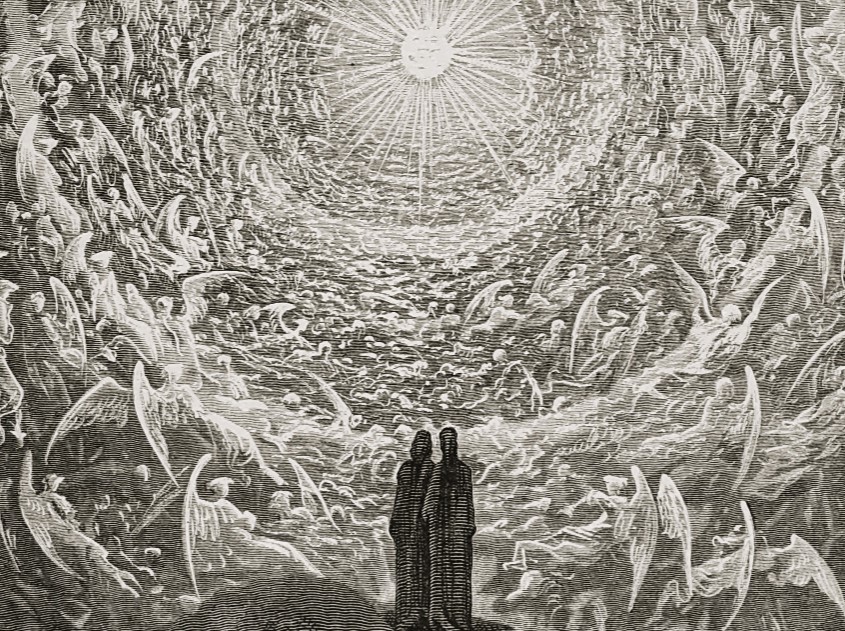

[Image: “Canto XXXI” in The Divine Comedy by Dante, Illustrated, Complete, via Wikipedia; File:Paradiso Canto 31.jpg – Wikipedia]

Some Christians will be scandalized by my promotion of traditional Cherokee Indian beliefs on this website. Charges of “syncretism” will probably be leveled, along with repetitions of Psalm 95:5 (“For all the gods of the Gentiles are devils”). What I’m attempting to do here, however, is simply what Catholic and Orthodox Christians have always done when they’ve encountered new cultures. In the “Universal History” tradition (as popularized by Richard Rohlin and Jonathan Pageau), richly exemplified for us in places like medieval Ireland, or within Dante’s Divine Comedy, Christians have engaged in a process of bringing all things together in Christ (Ephesians 1:10). What was good, true, and beautiful in the pre-Christian cultures they encountered, they preserved and incorporated. What was well-intentioned but mistaken, they corrected. And only what was clearly demonic or evil did they banish. It is only this three-fold process that I seek to inaugurate with regard to American Indian mythology and culture.

This never happened in North America, sadly, because Protestants were ultimately the ones who left their mark on the Indians and their land. Protestantism has many virtues, but it does not have assimilative power in the way that Catholicism does. Its black and white internal logic is premised on excision rather than inclusion. Consequently it must erase other beliefs and stamp itself in toto or not at all. In Protestantism, purity and simplicity of doctrine results in purity spiraling in culture and ethnic removal in space. It’s too nervous and self-conscious to offer a big tent because there are too many superstitions hiding around every corner.

Catholicism (and Orthodoxy), on the other hand, feel themselves old and established enough to flirt with the danger that comes from not exterminating rival belief systems. They just swallow them and digest them in a very organic way. Not everything must be known or definitively accepted or rejected. Some things can remain gray. There is no definitive teaching in Catholicism on what fairies are, for instance. But there’s a great body of folk belief and practice regarding them, and this provides the springboard for my project.

Protestantism was also incapable of dealing with Native beliefs because the Native beliefs were pre-modern, or traditional. Protestantism is partway down the road of the Enlightenment, and the Enlightenment (or Modernism, or “rational reductionism”) sees the traditional worldview as either foolish or incomprehensible. It cannot compute anything other than empirical, physical cause and effect, and it thinks it doesn’t need to. The traditional worldview, on the other hand, posits agency at every level of reality. This is what’s called “enchantment.” Protestantism limits enchantment to the mind (thus its iconoclasm).

The disenchanted Protestants and secular anthropologists therefore dismissed Indian beliefs about the multi-layered intelligences that govern the world as “superstition.” Indeed, this has been the cudgel used against all traditional belief systems, including Catholicism, for 500 years now.

Conservatives, traditionalists, communitarians, and indigenous peoples activists are all now engaged in a collective purging of Enlightenment mental bondage. At every turn we find some way in which liberalism, rather than our professed belief systems, has hitherto ensnared us without our knowledge. The battle against this intellectual colonialism has many fronts, but the chief one I would like to open up on this website straddles the imaginative, mythological, and historical spheres.

Landscapes must have a mythico-spiritual dimension. Go to Ireland and hear of the holy wells; the fairy forts; the portals to Purgatory and the underworld. Go to Ethiopia and interview the witnesses of a mermaid sighting. Climb Mount Mikami in Japan, once home to a voracious giant centipede demon, or visit the Ise Shrine and glimpse the sword Hidesato used to chop up the beast. Today, as a man purging Enlightenment reductionism from my psyche, I choose to put these sources of information on a level playing field with all other sources. Postmodernism has shown us the games that even official scientific knowledge plays with power and obfuscation, so I refuse its hegemony over other, incommensurate spheres.

But how “true” is mythology, you still want to ask? The answer, under the emerging paradigm of metamodern traditionalism, is fundamentally true at least, and literally true until proven otherwise. Give tradition the same benefit of the doubt you give any other source of information. As Christians we know the “sons of God,” spirit beings, have delegated authority over all that is (Deuteronomy 32:8). We know they can take physical form and even procreate with humans (Genesis 6:2). And we know from centuries of praxis and experience in Europe that earth spirits, or fairies, occupy an intermediate place between angels and demons, and that they seem very much “in process,” as we are, either toward virtue or vice. With these preliminaries we can begin to make sense of the data that world paganism supplied from pre-Christian times.

Many pagan gods probably were/are demons, or at least “fae” (or fairy) spirits who warped themselves through rebellion into something very similar. But there’s certainly much that could not reasonably be classed as “evil,” and so the idea of intermediate, morally complex spirits becomes useful. Just read The Illiad and see the moral confusion of the Greek panoply. These seem to me to be fae spirits haunting the craggy peaks of Mt. Olympus, and given dominion over the Greek people, though arguably abusing this power subsequently through history.

The Cherokee believed in a “Great Spirit,” and the beings they dealt with seemed even less problematic in some ways than the Greek gods. But there were certainly demonic entities they contended with. There were also great guardians of animalkind, who manifested as monstrous versions of their charges—the giant frog that still guards the passes around the lower spurs of Mt. LeConte, in the Great Smoky Mountains, for instance.

I detail in another article how traditional Christians might deal with all these mysterious (and sometimes frightening) spiritual realities. My purpose in this introduction is to give a defense of the concept of universal Christian history, and to propose an extension of this project to the exciting and beautiful world of the Cherokee Indian people, to whom we settlers of the Upper South owe so much.